|

newsletter — May 16, 2017

Advocating for oneself — Part 1

How adolescents learn to stand up for themselves

by Diane Speed

WHEN I WAS JUST starting out as a home-educator, a homeschooling mom told me about a local university that accepted high-school-age students in many of its classes. WHEN I WAS JUST starting out as a home-educator, a homeschooling mom told me about a local university that accepted high-school-age students in many of its classes.

She also told me that initially she was concerned that her own teenager would not get fair treatment there. So on the first day of class, she walked her student to the assigned classroom and asked to speak privately with the professor. She explained that her student was not a college student but a high-school-age teen who had been homeschooled, and she was alerting the professor to these facts in case the student exhibited any behaviors out of the norm — shyness, confusion, less worldliness.

At the time I never doubted this mom's good intentions, but I couldn't help thinking that she was preventing her student from experiencing and learning in the real world.

My conviction was then — and remains today — that:

- We must prepare our students to cultivate mature relationships with their teachers — to speak up for themselves.

- Classes taken outside our homeschool — and especially college classes — are great training grounds for developing such relationships and all the attendant skills.

Three skills your student needs

to develop before college

For homeschooled students, many important skills are best learned through classroom experience outside the home — skills like:

- taking lecture notes — a vital skill in college, and one we've written about previously;

- managing multiple deliverables — a skill that's challenging even for adults, but especially challenging for students unaccustomed to juggling assignments and deadlines for several courses at once;

- advocating for themselves — which is the topic of this newsletter.

In other words, I felt this mom was squandering a vital opportunity, depriving her student of an important experience: the opportunity to advocate for himself.

Our son — trouble with a professor

Our own son eventually took a number of college courses; in fact, he was still taking local college courses while applying to colleges around the country.

He was fortunate enough to become a candidate for a full scholarship (tuition, room, & board) at his number-one choice! The school invited him out to California to a weekend of on-campus activities and interviews. — But there was a problem:

To get there in time for the weekend activities, he would have to fly out on the day of his mid-term exam at a local university, and his professor was unmoved by his scholarship potential; if he missed her exam, she would give him an "F."

My husband and I found this nerve-wracking, but at no point did we intervene or speak to the professor; our son handled the whole situation himself. We coached him, of course; we counselled him to the best of our abilities. But he met alone with the professor and, in the end, came up with a solution she could live with: he would take the exam under her supervision during her office hours.

My husband and I felt grateful that our son could begin learning such important skills, gain such valuable experience, while still under our roof!

The fact is, this stage of our students' growth is a rite of passage for the parent as much as for the student. It involves separation: the parent must be willing for her student to become an adult — and part of becoming an adult is facing problems, taking responsibility for oneself, finding solutions to real conflicts.

What it is — and what it is not What it is — and what it is not

So by "advocating for oneself," I mean our students' ability to fend for themselves in their dealings with adults, with those in authority of some kind — teachers, college professors, college administrators, employers, and the like.

"Advocating for oneself" means:

- communicating — and often negotiating — with such adults;

- cultivating relationships with them;

- building credibility with them.

The problem is that few students, left to their own devices, will see how high the stakes are — the benefits of cultivating relationships with adults, e.g., the potential value of an adult mentor's guidance. Nor have they the experience needed to imagine the costs of not having such relationships.

All too often, we see teens who, rather than advocate for themselves, will —

- take pains to avoid contact with their teachers;

- be shy, with no urgency to push past their shyness;

- procrastinate when facing problems or conflicts, or try to evade them altogether;

- conceal their own mistakes, or shortcomings, or uncertainties, or ignorance.

Homeschooled vs. public school students

Now you've probably already noticed that homeschooled students often have a natural advantage in their dealings with adults: students who have never done time in the public school system have never absorbed the false values and wrongheaded norms that often prevail there.

The fact is, students in the school system often seem to view all adults, including their teachers, as adversaries: it's us against them. They've learned from an early age that the smart move is to game the system at every turn; it's what the cool kids do. The teacher or the coach or the principal is part of the system and therefore to be deceived, placated, jollied along, or even treated with open hostility; the notion of being sincere and open, of developing real relationships with such adults, based on mutual respect, may be a foreign concept — one that never enters their minds.

The shame of it is that students who fall into this mindset not only distance themselves from their teachers; they may never develop a real commitment to learning, never become real students.

Fortunately, as a result of homeschooling, many of our students don't have to overcome this mindset. They're accustomed to dealing with adults, and they're already inclined to view teachers as allies and, best of all, mentors who can guide them through the labyrinth of learning. For a student with this mindset, a healthy relationship with a teacher can then become a template for other important relationships with adults — like relationships with employers.

The strategy: Invest in adult relationships

So we parents must encourage our students to invest in their relationships with adults.

Such investments are like savings accounts: make regular deposits, and you will one day reap the benefits. College professors, for example, often learn of opportunities students aren't necessarily aware of — fellowships, research projects, internships, special programs involving study abroad, and so on. The students whom professors steer toward those opportunities will most likely be students they're already in relationship with — and especially students they've come to like and respect.

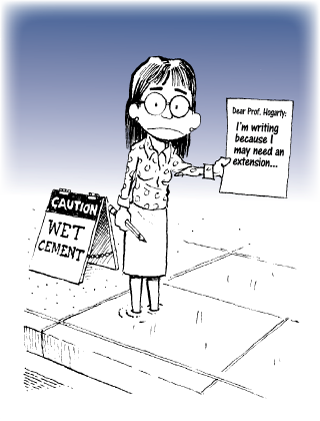

There's another type of benefit that comes from strong relationships with teachers — a benefit your student will need if something ever goes wrong. Imagine, for instance, that while at college, your student encounters a crisis of some sort and is likely to miss a deadline for a report or essay. In that circumstance, a student who is in relationship with the teacher — and has already earned his or her respect — can draw on that account, request that he or she bend the rules or relax a requirement, and that student may find the teacher surprisingly cooperative, even encouraging. There's another type of benefit that comes from strong relationships with teachers — a benefit your student will need if something ever goes wrong. Imagine, for instance, that while at college, your student encounters a crisis of some sort and is likely to miss a deadline for a report or essay. In that circumstance, a student who is in relationship with the teacher — and has already earned his or her respect — can draw on that account, request that he or she bend the rules or relax a requirement, and that student may find the teacher surprisingly cooperative, even encouraging.

Now there are a number of learnable skills and practices vital to cultivating a strong relationship with a teacher. What follows is our guide to these skills and practices.

Classroom skills & practices

Our students' advocating for themselves begins with their behavior in the classroom — and here we have in mind both physical classrooms and online classes.

We're often surprised when, at the end of a semester-long class, a parent tells us, Emma says this was the best class she's ever taken. She loved every minute of it… Yet from our perspective, as Emma's teachers, she was silent and seemingly unengaged throughout the entire course.

The point is, being engaged is not sufficient. Your student must be visibly engaged, an active participant. We recommend that parents coach their students to do all of the following:

- Ask questions. Honest questions bring you into relationship with the teacher, signal your readiness for dialogue. Honest questions also indicate your genuine engagement with, interest in, curiosity about the subject matter of the course — and to a good teacher, few things are more welcome than intellectual curiosity.

- Don't hang back. Some students are reluctant to jump into class discussions. In our experience, such shyness is usually traceable to students' fear of being judged, i.e., they're not as smart as other students, not as articulate, insightful, or original. Parents can help by simply getting their students to voice these fears, tell the truth: they want to be liked, and respected; they don't want to seem stupid... For some students, simply voicing these fears can help loosen them up. The key is that they be honest with themselves about what makes them hang back.

Now a student may make reasonable-sounding excuses, telling his or her parents things like There was something I wanted to say, but another student said it first... — when what actually happened was something like this: The student hung back, waited, and waited, watching the other students volley ideas and observations, and someone eventually said what the student was thinking. — So Another student said it first..., though technically accurate, is not honest reporting.

- Insist on understanding. When something doesn't make sense to you, engage with the teacher about the point you don't understand. — And take heart: If you don't understand it, it's likely that others don't as well, and you'll be the one who had the courage to say I don't understand. The teacher will respect you for it.

* * *

Coming in Part 2

Soon we hope to send out the second part of "Advocating for Oneself." — In that part, we'll address: Soon we hope to send out the second part of "Advocating for Oneself." — In that part, we'll address:

- College admissions — including interviews with admissions officers, college application essays (including essays for the Common App), and interviews or essays about scholarships;

- Meeting with a professor, advisor, or administrator — including being honest, being responsible, and not overpromising;

- Writing effective email — because you'd be surprised at the percentage of our students' direct contact with professors, administrators, and the like that takes place via email.

In the meantime, we have written in the past about college admissions — you may find it helpful to revisit that piece.

* * *

Not on our mailing list? — Adding yourself is easy; just go here.

|

|

|

View all our online courses here.

Eight weeks, in depth, live & online

Twice weekly sessions for two semesters

Twice weekly sessions for two semesters

- March 7, 2020: Beyond the Tour: Getting the most from your college visits

- July 29, 2019: Advocating for oneself, Part 2: College admissions essays & interviews

- May 29, 2019: What our students aren't taught about grammar

- May 16, 2017: Advocating for oneself (Part 1 of 2)

- July 20, 2016: The development of adolescent minds

- December 24, 2015: The appeal of videogames—and the hazards they bring

- August 16, 2015: Three skills your student needs to develop before college (Part 1 of 3)

- July 3, 2015: How literature is now taught in college—and why enrollment in literature courses is in steep decline

- June 1, 2015: Teaching Shakespeare to your kids: What I've learned

- Dec 28, 2014: Extracurricular activities, Part 2

- July 27, 2014: Levels of annotation —

Annotating the text, Part 2

- July 15, 2014: Extracurricular activities, Part 1

- July 2, 2014: Teens need to be together… An innovative solution

- June 9, 2014: The college admissions racket — Getting things into perspective

- June 2, 2014: Building good study habits

— Annotating the text, Part 1

- April 8, 2014: Building good study habits

— Close reading

- March 18, 2014: Why all our students must study Shakespeare

- Feb 25, 2014: Standardized tests, Part 2

- Feb 18, 2014: Standardized tests, Part 1

- Feb 1, 2014: Advanced mathematics

|

|

Shakespeare Intensives

Close reading of Shakespeare

Ten online sessions of 90 minutes

Ten online sessions of 90 minutes

Seven online sessions of 90 minutes

An introduction to Shakespeare's comedy

Eight online sessions of 90 minutes

ONLINE: English Language Arts

— Now open for registration —

Weekly online class

in the essentials of English

This two-semester course is taught by the author of The Writer's Guide to Grammar. It puts in place skills and knowledge foundational to the study of English and the mastery of clear writing. The weekly class is live and online, and students master all the most important principles of the English language — grammar, usage, punctuation, and more. This two-semester course is taught by the author of The Writer's Guide to Grammar. It puts in place skills and knowledge foundational to the study of English and the mastery of clear writing. The weekly class is live and online, and students master all the most important principles of the English language — grammar, usage, punctuation, and more.

Online Writing

Two semesters of online classes

Two classes per week

Online Literature

Two semesters of online instruction

Training for parents

Now an online series!

This program addresses the principal concerns parents have about homeschooling through high school — curriculum and credits, standardized tests, transcripts and record-keeping, the application process, pursuing scholarships, and more.

Terrific. Full of information. The materials were so thorough. I now have a plan of action. Also, this workshop is inclusive: No matter what type of homeschooler you are, you will understand better how to prepare your student for college and present him or her in the best light.

Mother of two

|

|

![]()