|

newsletter — July 27, 2014: more on "Digging In"

Levels of annotation

Students who annotate books make them their own

by Roy Speed by Roy Speed

Note: In our series "Digging In," we've been taking a close look at the foundational skills students will need both in college and later, in their professional lives — i.e., study skills:

In this piece, we're taking a closer look at your own student's annotations.

When I ask homeschooled students to annotate their texts, they often prove remarkably innocent about what I'm asking for. I've had students ask me whether they must annotate books they read for fun, take to the beach, etc.

I find that for homeschooled students, I must paint the entire picture of what it looks like to be a college student facing an exam. So in all my college-prep courses, I now preface my requests for annotation with the following speech:

At exam time, college students face a test that will ask them to recall all the important bits from weeks of study: not one chapter, but many chapters of their biology text, or their economics text; not one 470-page Victorian novel, but several such novels. In the week leading up to the exam, they can't simply re-read everything; there's no time, even if they don't sleep a wink. Besides, in addition to the biology class or the class on the Victorian novel, they have three or four other classes to study for, all at the same time. — So how do they manage it?

They make the challenge manageable from the start by annotating each text as they study. Students who annotate a book leave themselves a breadcrumb trail through the entire text, marking all the steps along their path to understanding and digesting its contents. Good annotations are ones that enable students to quickly retrace their steps, quickly locate every important concept or piece of information and skip over the stuff that's less important. They're trails that are easy to follow. They haul all the buried treasure into plain sight. They make the challenge manageable from the start by annotating each text as they study. Students who annotate a book leave themselves a breadcrumb trail through the entire text, marking all the steps along their path to understanding and digesting its contents. Good annotations are ones that enable students to quickly retrace their steps, quickly locate every important concept or piece of information and skip over the stuff that's less important. They're trails that are easy to follow. They haul all the buried treasure into plain sight.

So at exam time, or when they're getting ready to write a paper, effective students don't study the entire text. They study their own annotations of the text.

The larger point here is that most homeschooling parents are raising their kids in an exam-free environment. As a result, the need for disciplined study skills is not at all obvious to our students, and those skills won't organically develop on their own. — The good news:

- Annotation is perfectly teachable.

- When it's taught as an aid to close reading, students quickly come to appreciate its value.

Levels of annotation

Your own student's annotations will usually mirror with remarkable precision his or her level of engagement with the text. Working with homeschooled students, I have observed four distinct levels:

Levels of Annotation: At a glance

Level 0

No annotations

|

- The student neither marks up books nor takes notes on the text.

- Likely explanation: Student doesn't see the need.

|

Level 1

Highlighting & flagging

|

- The student simply highlights or underlines passages, with no scribbled notes on those passages.

- Likely explanation: Student has an inadequate understanding of what's needed to 1) digest a book's contents and 2) prepare for papers or exams.

|

Level 2

Paraphrasing & structuring

|

- The student highlights, underlines, and paraphrases in the margins.

- Student is beginning to engage with the text. The challenge is to go deeper.

|

Level 3

Insights & connections

|

- The student does everything at Levels 1 & 2 above, but also records insights, indicates connections to other passages within the same work, and even draws connections to other works.

|

Now for a closer look at each level. — Notice your own student's level of engagement, where he or she hangs out the most, and examine the more detailed discussion of that level below:

- Level Zero: No annotations. Your student has just completed reading a heavy-duty book of some sort — say, a Russian novel or an economics text — and the pages are pristine, free of highlighting or other marks or scribbling. This level of annotation usually suggests superficial engagement with the content.

Where study skills are concerned, the student is expressing either:

- supreme confidence — complete confidence in her ability to recall the book's contents;

- utter naïveté — complete unawareness of the need for such recollection.

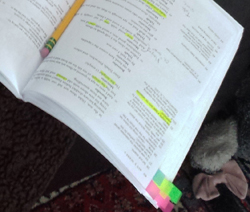

Level 1: Highlighting & flagging. The first time students mark a text, they may reach for a highlighter — a simple tool that suits perfectly this most basic level of annotation. Level 1: Highlighting & flagging. The first time students mark a text, they may reach for a highlighter — a simple tool that suits perfectly this most basic level of annotation.

What it does for the student: Not that much, unfortunately. By highlighting a passage (or by underlining it, or by turning down the corner of a page) the student is saying to him- or herself: This is worth noting. — Highlighting another passage sends the same signal: This, too, is worth noting…

The downside: This signal is too vague, uninformative. When students return to the text a month or so after highlighting it, they may wonder Why did I highlight this? — They must then reread the surrounding text to discern what they felt was noteworthy.

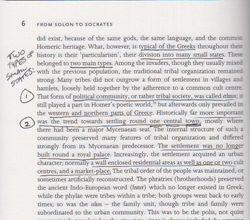

Bottom line: This type of breadcrumb trail is too faint to follow. Level 2: Paraphrasing & structuring. Students annotating at this level not only highlight, underline, and flag important passages; they scribble in the margins their own paraphrase of each passage. They may also try to organize or structure difficult information, to make that structure easier to perceive or understand on a return visit (an example with a history text is shown at right). Level 2: Paraphrasing & structuring. Students annotating at this level not only highlight, underline, and flag important passages; they scribble in the margins their own paraphrase of each passage. They may also try to organize or structure difficult information, to make that structure easier to perceive or understand on a return visit (an example with a history text is shown at right).

Limitations: Annotations at this level reflect the student's grappling with his or her literal understanding of the text — a stage every student must pass through and succeed with before going any deeper. The problem: When the student's annotations reach this stage and go no further, it means other thoughts or insights the student might be having are not being recorded, are not making their way into the annotations. Level 3: Insights & connections. Students at this level do everything described above, but they also use their annotations to record insights, use arrows to indicate connections among different passages, and even insert page and line references to other parts of the text with some bearing on the current page. They may also insert: Level 3: Insights & connections. Students at this level do everything described above, but they also use their annotations to record insights, use arrows to indicate connections among different passages, and even insert page and line references to other parts of the text with some bearing on the current page. They may also insert:

1) counterarguments to the author's points;

2) references to other works;

3) the author's omission of important facts or views.

Implications: The student is using annotations to move beyond literal understanding and record his or her own creative thinking about the text and the author. Equally important:

- The student is breaking out of the confines of any one passage to forge mental connections to other parts of the text, to other texts entirely, or to other knowledge.

- The student's personal copy becomes an indispensable study guide — one the student would be sorry to lose.

Recommended reading for your student. In 1940 Mortimer Adler wrote

the book How to Read a Book and included a chapter called "How to Mark a Book."

See here for our adapted and streamlined version of this useful chapter. |

Understanding your own student

These levels of annotation provide a sort of prism through which you can view your student, discern her current level, and begin to intuit how to encourage and coax her to the next level.

In practice, your student may move among these levels — briefly popping up to Level 3 (insights and connections), and then falling back to Level 2 or even Level 1 (mere underlining or highlighting).

You may even notice patterns like the following:

- With a science text, your student annotates at Level 3.

- With literature, he or she never moves beyond Level 1 or 2.

— or vice versa.

Now for the good news

Our students can be taught to annotate.

In my Shakespeare classes, for instance, I now discuss annotation in the first couple of sessions, and then in each class, I model close reading and challenge the students to look beneath the surface of each character, each scene. Then, about mid-way through the series, I require that students send me scans of particular pages from their text — specifically so that I can review their annotations. The aim, of course, is that by the end of the series, each student not only sees the value of annotating, but has begun to develop the habit.

Finally, in my course evaluations I now include the following question:

Did you learn anything in this course that you think will benefit you in your future studies? (Please describe.)

Here's how my students now answer this question (emphasis mine):

I learned valuable skills for studying literature. I can now better annotate the texts that I work out of.

My annotating skills and being able to decipher and understand Shakespeare will help me tremendously in future reading of Shakespeare plays and regular books.

How to thoroughly annotate a book and taking notes from your lectures.

The idea of annotating books and making them your own. I would imagine that this is a skill that will help me through life!

Yes. I started noticing more details in the story, and I learned how to really get into annotating.

How to annotate like there's no tomorrow.

* * *

Not on our mailing list? — Adding yourself is easy; just go here.

|

|

|

View all our online courses here.

Eight weeks, in depth, live & online

Twice weekly sessions for two semesters

Twice weekly sessions for two semesters

- March 7, 2020: Beyond the Tour: Getting the most from your college visits

- July 29, 2019: Advocating for oneself, Part 2: College admissions essays & interviews

- May 29, 2019: What our students aren't taught about grammar

- May 16, 2017: Advocating for oneself (Part 1 of 2)

- July 20, 2016: The development of adolescent minds

- December 24, 2015: The appeal of videogames—and the hazards they bring

- August 16, 2015: Three skills your student needs to develop before college (Part 1 of 3)

- July 3, 2015: How literature is now taught in college—and why enrollment in literature courses is in steep decline

- June 1, 2015: Teaching Shakespeare to your kids: What I've learned

- Dec 28, 2014: Extracurricular activities, Part 2

- July 27, 2014: Levels of annotation —

Annotating the text, Part 2

- July 15, 2014: Extracurricular activities, Part 1

- July 2, 2014: Teens need to be together… An innovative solution

- June 9, 2014: The college admissions racket — Getting things into perspective

- June 2, 2014: Building good study habits

— Annotating the text, Part 1

- April 8, 2014: Building good study habits

— Close reading

- March 18, 2014: Why all our students must study Shakespeare

- Feb 25, 2014: Standardized tests, Part 2

- Feb 18, 2014: Standardized tests, Part 1

- Feb 1, 2014: Advanced mathematics

|

|

Shakespeare Intensives

Close reading of Shakespeare

Ten online sessions of 90 minutes

Ten online sessions of 90 minutes

Seven online sessions of 90 minutes

An introduction to Shakespeare's comedy

Eight online sessions of 90 minutes

ONLINE: English Language Arts

— Now open for registration —

Weekly online class

in the essentials of English

This two-semester course is taught by the author of The Writer's Guide to Grammar. It puts in place skills and knowledge foundational to the study of English and the mastery of clear writing. The weekly class is live and online, and students master all the most important principles of the English language — grammar, usage, punctuation, and more. This two-semester course is taught by the author of The Writer's Guide to Grammar. It puts in place skills and knowledge foundational to the study of English and the mastery of clear writing. The weekly class is live and online, and students master all the most important principles of the English language — grammar, usage, punctuation, and more.

Online Writing

Two semesters of online classes

Two classes per week

Online Literature

Two semesters of online instruction

Training for parents

Now an online series!

This program addresses the principal concerns parents have about homeschooling through high school — curriculum and credits, standardized tests, transcripts and record-keeping, the application process, pursuing scholarships, and more.

Terrific. Full of information. The materials were so thorough. I now have a plan of action. Also, this workshop is inclusive: No matter what type of homeschooler you are, you will understand better how to prepare your student for college and present him or her in the best light.

Mother of two

|

|

![]()