|

newsletter — July 20, 2016

The development of adolescent minds

by Diane & Roy Speed by Diane & Roy Speed

Most applications of chemistry are oriented towards the interpretation of observations and the solving of problems. In these endeavors, memorization of facts may be of some aid, but most important to the study of chemistry is the ability to combine, relate, and synthesize information.

Steven S. Zumdahl

Introductory Chemistry: A Foundation

During the high school years, home educators wrestle with defining and delivering the right content. They consider scope and sequence of traditional subjects — geometry, chemistry, literature, etc. — along with how best to deliver all that content… Online? — through co-ops? tutors? community colleges? And in some families, these deliberations are mingled with questions about each subject's practicality:

- Will my teen ever need trigonometry?

- Mom, I'm not going to be a scientist, so why do I have to study physics?

- Mom, I'm gonna be an engineer, so why do I have to read Jane Austen?

In this maelstrom of deliberations and decisions, it's easy to lose sight of something really important: developing the minds of adolescents is not just about the content of the high school curriculum — the knowledge or information contained in that curriculum. The stakes are much higher than mere data, much of which will be forgotten within a few years.

It's no accident that we open with a quote from Zumdahl's Introductory Chemistry — what he says about the study of chemistry could be said of many high school subjects: the principal challenge is not mere memorization of facts; rather, it is to combine, relate, and synthesize those facts. This sort of higher-level thinking is not something your sixth- or seventh-grader ever had to do. It's no accident that we open with a quote from Zumdahl's Introductory Chemistry — what he says about the study of chemistry could be said of many high school subjects: the principal challenge is not mere memorization of facts; rather, it is to combine, relate, and synthesize those facts. This sort of higher-level thinking is not something your sixth- or seventh-grader ever had to do.

The point is that across the high school curriculum, our teens are asked to perform mental tasks that, to their adolescent minds, are entirely new kinds of intellectual challenges. To be effective as homeschooling parents, we must not only see clearly this landscape of challenges; we must understand the benefits those challenges bring to our students.

Great resources

One helpful book on the subject is Smart but Scattered Teens, by Richard & Colin Guare and Peg Dawson. The authors outline 11 "executive skills" that our teens will need as adults, in order to be effective in their lives. If you have a teenager in your family, reading this book will likely prompt repeated experiences of recognition: Yup, that's my kid all right…

Roy and I have also found that a perennially useful resource for understanding student development is The Well-Trained Mind by Jesse Wise and Susan Wise-Bauer. The authors provide a useful perspective on the development of the mind — what they call the Trivium, the theory that our minds develop in three discrete stages (a model you can also read about here).

The second level of the Trivium — known as the "Logic" stage — is the level most of our teens are entering: at this stage, they develop the ability to think abstractly, synthesize ideas, evaluate evidence, and so on. These are all abilities that most little kids don't have and, more important, are not yet capable of developing. Yet our teens are capable, and we owe it to them to challenge them academically, in order to develop these mental muscles. The second level of the Trivium — known as the "Logic" stage — is the level most of our teens are entering: at this stage, they develop the ability to think abstractly, synthesize ideas, evaluate evidence, and so on. These are all abilities that most little kids don't have and, more important, are not yet capable of developing. Yet our teens are capable, and we owe it to them to challenge them academically, in order to develop these mental muscles.

The high school landscape

As Roy and I have seen countless times with the students we teach, our teens are simultaneously grappling with diverse new skills and challenges. Here's an overview of this landscape:

- analysis and synthesis

- logical arrangement/organization of ideas;

- effective expression of ideas;

- organizational skills, like planning, prioritizing, and decision-making;

- study skills, like taking clear notes (see here), close reading (see here), annotating texts (see here), expanded working memory, and sustained concentration;

- emotional challenges, including self-awareness and self-evaluation, regulating feelings, and exercising judgment about acting on feelings.

We have written at length on some of these skills or challenges — the links above are to our previous newsletters on study skills — and we will write more in the future. For now, we'll limit ourselves to exploring one dimension of these skills: analysis and synthesis. We have written at length on some of these skills or challenges — the links above are to our previous newsletters on study skills — and we will write more in the future. For now, we'll limit ourselves to exploring one dimension of these skills: analysis and synthesis.

Analysis and synthesis

This is the intellectual challenge Zumdahl was describing in the introduction to his chemistry text, but it's usually discussed as though it were a dry exercise in pure logic. It's not.

Consider, for instance, how differently high school students must exercise their imaginations.

As little kids, many students populated their imaginations primarily with stories. Little-kid minds are so attuned to stories, in fact, that lots of information is packaged for them in the form of stories — just notice how frequently history for children makes use of the story form, and how readily children absorb biographies, which lend themselves to storytelling.

But once our students reach high school age, they're asked to imagine in entirely different ways, ways that may be intellectually daunting:

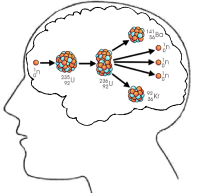

Science. In biology, students must master large quantities of information on cellular entities, cellular processes, and complex biochemical reactions — but it's all invisible. Sure, all the text books have colorful illustrations of cell structures and nice diagrams of organic molecules. But students, in order to complete their mental picture of cellular functions, must imagine those processes in action. Science. In biology, students must master large quantities of information on cellular entities, cellular processes, and complex biochemical reactions — but it's all invisible. Sure, all the text books have colorful illustrations of cell structures and nice diagrams of organic molecules. But students, in order to complete their mental picture of cellular functions, must imagine those processes in action.

In a similar challenge, they must imagine the scale: those processes are happening invisibly inside each of us, all the time, in billions of cells. The interior of a single human body is like an entire universe.

In chemistry, students encounter a similar challenge, only now the players are atoms and sub-atomic particles. In a chemistry lab, combining two substances may produce a rise in temperature — but the students' challenge is to apply what they've learned about those substances to imagine what's going on, unseen, at the atomic level: What's happening that could produce heat? — This is what Zumdahl has in mind when he refers to analysis and synthesis; mere facts are just the starting point. The real work is what the students do with those facts.  History. The intellectual challenge of history, again, is not the mastery of mere facts, but the assembly of those facts into a coherent mental picture of human activity in distant times and distant lands. It requires synthesis of many different types of facts: geography, economics, agriculture, engineering & architecture, language, politics & statesmanship, warfare, etc.; then it requires a deliberate act of imagination to re-create in your mind the historical reality. History. The intellectual challenge of history, again, is not the mastery of mere facts, but the assembly of those facts into a coherent mental picture of human activity in distant times and distant lands. It requires synthesis of many different types of facts: geography, economics, agriculture, engineering & architecture, language, politics & statesmanship, warfare, etc.; then it requires a deliberate act of imagination to re-create in your mind the historical reality.

Consider, for instance, what's involved in re-imagining a single historical decision — like:

- the ancient Persians' decision to invade Greece — a really complex decision with deep roots (Herodotus traces it back to Helen of Troy);

- the ancient Romans' decision to build apartment buildings to unprecedented heights — for safety reasons, the emperor Augustus issued an ordinance limiting their height to 70 feet;

- the decision by the framers of the U.S. constitution to create the electoral college — which prevents presidents being elected by a simple majority vote;

— and so on. Again and again, high school students are asked not only to master historical facts but to weave them together into complex imaginative re-creations involving cause and effect, problems and solutions, theories and fact, evidence and logical inference, but also human needs, desires, and hidden motives, like greed, honor, or lust.

All this is thinking of a very high order.

What it all means

The fact that your student isn't going to be a scientist doesn't mean she shouldn't study chemistry; on the contrary, developmentally, it's critical that she grapple with the mental tasks required to study the sciences. Similarly, your budding engineer must read Jane Austen and Shakespeare.

It's the process of learning all this content — the implicit demands of wrestling with every subject in the curriculum, including foreign language, math, literature, essay writing — that will permanently improve the dynamism and agility of each student's mind.

What's more, those higher-level mental skills will endure — and continue to yield benefits — long after your student has forgotten the phylum to which starfish belong, the atomic number of carbon, or the year of Shakespeare's birth.

* * *

Not on our mailing list? — Adding yourself is easy; just go here.

|

|

|

View all our online courses here.

Eight weeks, in depth, live & online

Twice weekly sessions for two semesters

Twice weekly sessions for two semesters

- March 7, 2020: Beyond the Tour: Getting the most from your college visits

- July 29, 2019: Advocating for oneself, Part 2: College admissions essays & interviews

- May 29, 2019: What our students aren't taught about grammar

- May 16, 2017: Advocating for oneself (Part 1 of 2)

- July 20, 2016: The development of adolescent minds

- December 24, 2015: The appeal of videogames—and the hazards they bring

- August 16, 2015: Three skills your student needs to develop before college (Part 1 of 3)

- July 3, 2015: How literature is now taught in college—and why enrollment in literature courses is in steep decline

- June 1, 2015: Teaching Shakespeare to your kids: What I've learned

- Dec 28, 2014: Extracurricular activities, Part 2

- July 27, 2014: Levels of annotation —

Annotating the text, Part 2

- July 15, 2014: Extracurricular activities, Part 1

- July 2, 2014: Teens need to be together… An innovative solution

- June 9, 2014: The college admissions racket — Getting things into perspective

- June 2, 2014: Building good study habits

— Annotating the text, Part 1

- April 8, 2014: Building good study habits

— Close reading

- March 18, 2014: Why all our students must study Shakespeare

- Feb 25, 2014: Standardized tests, Part 2

- Feb 18, 2014: Standardized tests, Part 1

- Feb 1, 2014: Advanced mathematics

|

|

Shakespeare Intensives

Close reading of Shakespeare

Ten online sessions of 90 minutes

Ten online sessions of 90 minutes

Seven online sessions of 90 minutes

An introduction to Shakespeare's comedy

Eight online sessions of 90 minutes

ONLINE: English Language Arts

— Now open for registration —

Weekly online class

in the essentials of English

This two-semester course is taught by the author of The Writer's Guide to Grammar. It puts in place skills and knowledge foundational to the study of English and the mastery of clear writing. The weekly class is live and online, and students master all the most important principles of the English language — grammar, usage, punctuation, and more. This two-semester course is taught by the author of The Writer's Guide to Grammar. It puts in place skills and knowledge foundational to the study of English and the mastery of clear writing. The weekly class is live and online, and students master all the most important principles of the English language — grammar, usage, punctuation, and more.

Online Writing

Two semesters of online classes

Two classes per week

Online Literature

Two semesters of online instruction

Training for parents

Now an online series!

This program addresses the principal concerns parents have about homeschooling through high school — curriculum and credits, standardized tests, transcripts and record-keeping, the application process, pursuing scholarships, and more.

Terrific. Full of information. The materials were so thorough. I now have a plan of action. Also, this workshop is inclusive: No matter what type of homeschooler you are, you will understand better how to prepare your student for college and present him or her in the best light.

Mother of two

|

|

![]()